February 20-28th, 2017 (written at the end of the cruise)

We’ve all seen the travel brochure images of Antarctica … a cloudless sky with the sun illuminating the dazzling white snow, the deep blue of crevices in the ice and the tourist boat floating serenely, reflected amidst ice flows on an a azure blue see. Well, it’s not quite like that!

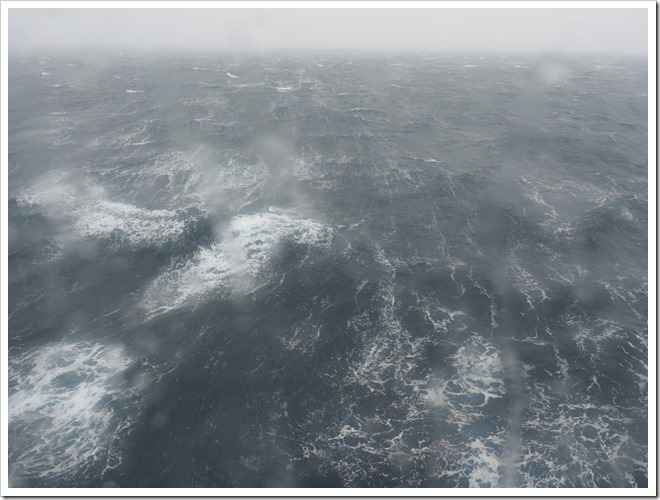

Along the coasts of the Peninsula, ninety percent of the time it was many shades of grey or blue-grey beneath an overcast sky of more shades of grey. And the sea was in no fit state to create any reflections, only our mental reflections on how it could be otherwise!

Does that detract from the scene before our eyes? No, not necessarily! What follows is a mental reflection on colour in the Antarctic …

Of course, where there is bare rock, either islands or mountains, there is brown, or may be just a very dark grey, splotched with white snow patches or blue-white hanging glaciers. But overall, it is a snow and ice environment, and white, blue-white and shades of grey in colour. However, one dull morning was magically bright, and I was suddenly seeing in black and white, Ansell Adams black and white! With high, clear contrast. I can’t wait to get to work on some of those images.

Another source of colour are of course are man-made things, and man and woman, too. There are several faded red emergency shelters dotting the coastline, and active research bases add their splash of colour. We expeditioners provide colour too. We had two-tone blue jackets, or some had bright red jackets. But these are exceptions; nature does not seem profligate with colour down here in Antarctica..

Sunshine does add a little warmth to the white snow, and makes the blues a little more intense. It is the blue of the sky that adds the colour, giving more blue than grey to the sea, and brightening the snow fields. An errant shaft of sunshine will highlight features in an otherwise dull scene.

Even a weak sun can add warmth and colour to the scene

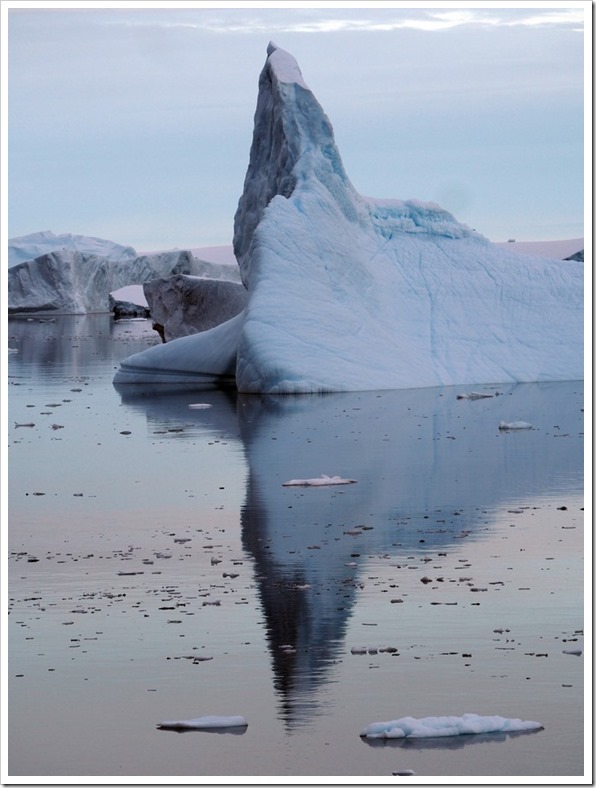

The lack of vibrancy of colour is compensated for by the infinite variety of shapes in the many glaciers and ice falls, and by the incredible sculptures created by repeated cycles of thawing and freezing of the countless icebergs, ice flows, berglets, brash ice, and tiny, tiny fragments of clear ice.

Amongst these sculptures our imagination could run riot! Here, floating in the water is a white whale, with its flukes and head above water. There, an unmistakable dragon. Over there a pure white seal sitting up on its front flippers, head pointed to the sky. On a larger scale there are battlements of amazing castles, or great floating mountains several hundreds of meters high.

Ice sculptures fire the imagination

All of these species of sea ice are in constant motion, blown by wind or carried by current – the seascape is very dynamic! And when all this glacial debris gets together in a little bay, and a mini tsunami caused by a glacier calving on the opposite shore passes through it, it jiggles and tinkles in a most amazing natural orchestra.

Brash ice, or glacial debris, has it’s own music when set in motion

Of course, there is the possibility of seeing a real whale! Or seals camped out on an ice flow, patrolling the cold clear water, or sitting serenely on front flippers, head to the sky, barking. One ice flow is like a jumping castle, and inside is a pool of clear blue-green water with three seals playing like human kids in a blow-up jumping castle at a show or fair. Schools of penguin are porposing at great speed so as to breathe while airborne. Occasionally a lone penguin sits in solitary confinement on the snow, or on an ice flow, serenely surveying its grey-white world, and seemingly unconcerned either by its isolation, or us. Or a dozen seals, or one, bask on their sides on the frigid surface of an ice flow.

The wildlife don’t seem to mind the isolatsion

The glaciers and major icebergs are another world. These are also dynamic, but on a much longer time scale. For glaciers it was millennia, as these great rivers of ice inexorably flowed under gravity, but with rising atmospheric temperatures their movement has in many cases speeded up because increased melt water acts as a lubricant . Apart from hanging glaciers on the mountain slopes, Antarctic glaciers come right down to sea level, and their tongue is often floating in the sea.

Ice caps and some glaciers come down to the sea and spawn icebergs

The mountain glaciers spawn avalanches when ice breaks away from their tongue, while the coastal glaciers spawn icebergs when they calve and great fragments of ice break off and float away for an independent existence. They can be carried vast distances by ocean currents before melting into obscurity. They are also wind blown despite the great mass of ice below the surface, and many an Antarctic expedition has felt their unrelenting pressure. Our progress through a channel was blocked by icebergs that had come from some where else, and some on-shore activities were curtailed by sudden wind changes threatening our passage back to the Polar Pioneer.

Icebergs … of all shapes and sizes

As glaciers flow under gravity they both erode away the underlying bed rock, which is why glacial rivers are so full of sediment, and flex up and down creating crevasses. Large icebergs preserve these crevasses, and as you travel past them you can see a range of blue colours in their interior. This colour is quite intense, almost fluorescent at times.

We all know snow is white … “as pure as the driven snow”! So why do we see this blue colour, and why are some berglets almost transparent, like the ice in a gin and tonic? It is similar to the reason the sky is blue. White light, the light all around us in day time, is actually many colours; these are displayed in a rainbow. If you shine white light it through some any substance, the light that emerges may be coloured because some of the colours have been removed, either by absorption or by scattering away from the direction in which you are looking.

Fresh snow is white because the minute snow flakes scatter the incoming light equally in all directions. The sky is blue because the air molecules and impurities in the atmosphere scatter blue light the least. Atmospheric gasses, e.g. oxygen, nitrogen and CO2, are absorbed by snow. As time passes and snow accumulates on the glacier, the lower layers are compressed and the gases in that snow become compressed into tiny bubbles. These then scatter incoming light, and blue light is scattered least … so the interior of the crevasse, where the snow is oldest, appears bluer. With higher pressure, or warming of the snow due to friction in the glacier, the snow can melt and refreeze as pure water ice with the tiny bubbles of gas frozen in place. This gives rise to the clear ice we often see floating around.

The varied colours of old ice

Old glaciers or ice sheets contain frozen in their snow and ice samples of the atmosphere from when the snow fell. Climatologist drill into the ice to extract cores from different depths and hence can determine how the atmosphere varied over time, over a time scale of thousands or hundreds of thousands of years!

I said we all know snow is white … but mostly. The Kiwis complain we Australians stain the snow in the New Zealand Alps brown during some summers. This is due to either dust or smoke pollution from storms and bush fires in Australia. Down here in Antarctica, we also saw a lot of red stained snow. Aussies are not to blame for this: it’s mainly penguin poo. Penguin colonies can be dirty (and smelly) places as penguins poo indiscriminately while going about their daily business. Their poo has a red colour from their diet of krill. The nutrients in pelican poo also enrich the snow which becomes a wonderful medium for algae to grow in. This algae comes in two forms: red algae and green algae, which also give the snow a quite strong red or green tinge.

So even on dull, grey days, there is colour! Over the 11 days of our voyage, we had had one morning of sunshine, and a sunset which enlivened both sky and water with reds and oranges.

Our last afternoon was sunny as we stood on the ice of the King George Island landing strip for an hour waiting to board our plane north to lands of vibrant greens, reds and blues. The air was crystal clear and the low hills and the central ice cap scintillated with travel brochure clarity …

No comments:

Post a Comment